As we settle into the summer season, our priorities may be focused on vacations, retreats from the busyness of daily life or maybe even planning for autumnal resolutions. Summer can also be a moment to reflect on spring’s bounty and its fruitful outcomes. From thriving flora, beauty and rebirth, spring reminded us of new beginnings, asparagus season, and some pending “spring cleaning” in our homes. Our Iranian community celebrated Nowruz, marking their official new year with the Spring equinox, by taking the opportunity to reflect on the past and set intentions for the future. There’s a cyclical nature and comforting predictability as we move between seasons. To whatever degree we experience the shift between seasons, it’s within these moments of transition that we’re often reminded of the passing of time and renewed life.

But as some of us in the northern hemisphere experience this season as a shift from the bounty of spring to the blazing summer, others in the southern hemisphere are feeling the chill and quiet of winter settling in. The cycle of life and death is an inevitable truth that underscores every organism on earth. The twin sister of life itself, death is often too discomforting to consider day to day. This is natural, given that loss, and the process of mourning, is one of the hardest things anyone can go through. Whilst some cultures treat funerals as ceremonies of grief adorned in black or white, others treat death as celebrations of a life well lived, or maintain regular contact with those who have transitioned to higher planes (take the Mexican Dia de los Muertos, or ancestral shrines found across Asia, as examples). Overall, there is something to be said about looking at death, or our limited life span, as a guiding reminder on how we want to live. If the pandemic taught us anything, it may have been that.

This piece is a reflection on how designing with death and lightness of being as cornerstones could increase our respect and protection for what is finite—our life on earth, our resources, and the time we have left to care for future generations. In other words, can integrating a regular dialogue about our own limited lifespan inspire us to reprioritise and act with greater urgency and do what will help ourselves and our planet to flourish?

According to the IPCC’s April 2022 report, we have 80 months (7 years) to limit Mother Earth’s warming to around 1.5°C (2.7°F). Last month, we heard global warming is likely to exceed 1.5 within 5 years. According to the IPCC, to limit global greenhouse gas emissions they need to peak before 2025 at the latest, and be reduced by 43% by 2030. We know that several industries in specific parts of the world are largely responsible for getting us here in the first place. These types of statistics can feel abstract and unsettling for those of us going about our day to day lives—trying to make a living, taking care of loved ones, ourselves… These types of headlines and a sense of hopelessness amidst the urgency at hand, can often leave us feeling paralyzed, or worse, indifferent.

The Doomsday clock, founded by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in 1947, was designed to estimate self-annihilation based on how many minutes we have until midnight. In January 2023, the clock was set at 90 seconds to midnight, the closest it’s ever reached. It was moved forward due to our current polycrisis: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, risk of nuclear escalation, the effects of climate change, the “unabated” disinformation online, and an ongoing threat of infectious disease outbreaks. Whilst the Bulletin has said the clock is not a forecasting tool, it symbolizes multiple threats to humanity. Would regular access to a similar clock in your home, and a reminder of our proximity to annihilation cause you to make greater efforts to protect our planet? Probably not.

A designer’s training is interdisciplinary. Each practice, in tandem with other fields of design and in collaboration with experts in given fields, has the capacity to influence behavioral change or behavioral consistency grounded in climate action. However, taking this doomsday clock as an example, the potential for behavioral change and environmental action from a visual reference alone, however much it may remind us of our time left on earth, is likely to be limited.

By contrast, behavioral change theorists believe the “region beta paradox” has great potential to catapult people into climate action. The RBP can be defined as the phenomenon that “people can sometimes recover more quickly from more distressing experiences than from less distressing ones,” i.e. that difficult events create better outcomes over time. Take what happened in South Africa with “Day Zero”as an example. Between 2017 and 2018, after three years of extreme drought, water supply for Cape Town’s four million citizens was under threat. The government responded with an information campaign that overcame skepticism and garnered support from socially and economically diverse Captonians, as well as private companies. As a result of the Day Zero campaign, combined with improved data management and upgraded technology, the drought eased in 2018. Citizens cut their water usage to nearly 60% from 2015 levels, with each resident using a little less than 50 liters per day. This demonstrates how effective a visual and accessible guide can be in converting the doom of climate crisis into actionable relatable steps to incorporate in one’s day to day life. As a result, Cape Town achieved one of the lowest per capita water consumption rates in any major city in the world.

Some metaphors can be used to make the impact of climate change feel less abstract, such as former vice president of the United States Al Gore’s example of a frog in a pot of water reaching boiling point, used in his book An Inconvenient Truth. The idea is that if a frog is put suddenly into boiling water, it will jump out, but if the frog is put in lukewarm water which is then brought to a boil slowly, it will not perceive the danger and will be cooked to death. This metaphor is often used to describe the inability or unwillingness of people to react to threats, such as the environmental crisis, that arise gradually rather than suddenly, (although biologists argue this isn’t accurate given frogs are smart enough to jump out). Despite willingness to react, for those whose day to day lives are not immediately (or obviously) impacted by the effects of climate change or the threat of a closer death, it could be more difficult to act with haste by way of necessity. Meanwhile the idea of death is often met with fear, instead of something to reflect upon and consider when it comes to the daily choices we make in protection of ourselves and the planet. With this in mind, is there potential for designers to treat the notion of death as a guide for what they make and how they may influence climate action? For example, could designers’ interdisciplinary expertise and ability to redesign products, services and experiences with death (or a finite life) as a cornerstone, facilitate the following:

For our lifespan

- Making practical, actionable steps to limit Mother Earth’s warming to 1.5°C in the next 5 years less abstract and more digestible for direct action

For the afterlife

- Enforcing a sense of purpose and responsibility to make a difference beyond our life span, to care for future lives after our time on earth

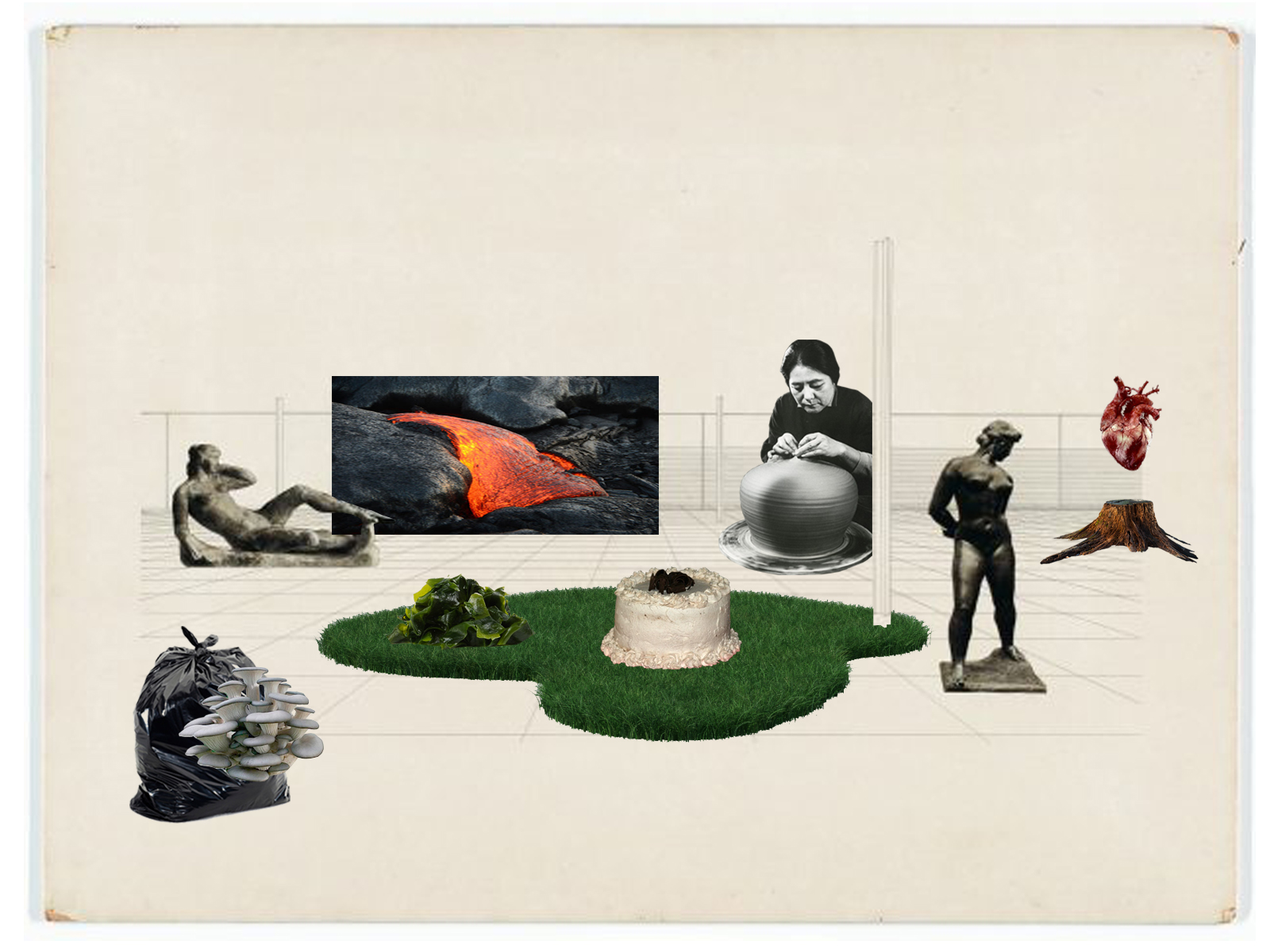

It is worth acknowledging that for both of the above actions to reach their fullest potential, they require us to embrace a fundamentally different way of being, grounded in lightness of being, less material possession, shared economies, a reframe of a luxurious life and what is deemed desirable and why. Design plays a huge role in shaping desirability and subsequently what is worth striving for, selling and buying. As one example of this logic, a “designer item” is interlinked with conspicuous consumption for those who wish to differentiate themselves based on their wealth and the material objects they own. Considering designers are curators of desirability, they hold the power to reframe luxury with living a light life before one’s death, instead of excessive wealth and material possession, which are deeply misconstrued with our notions of progress.

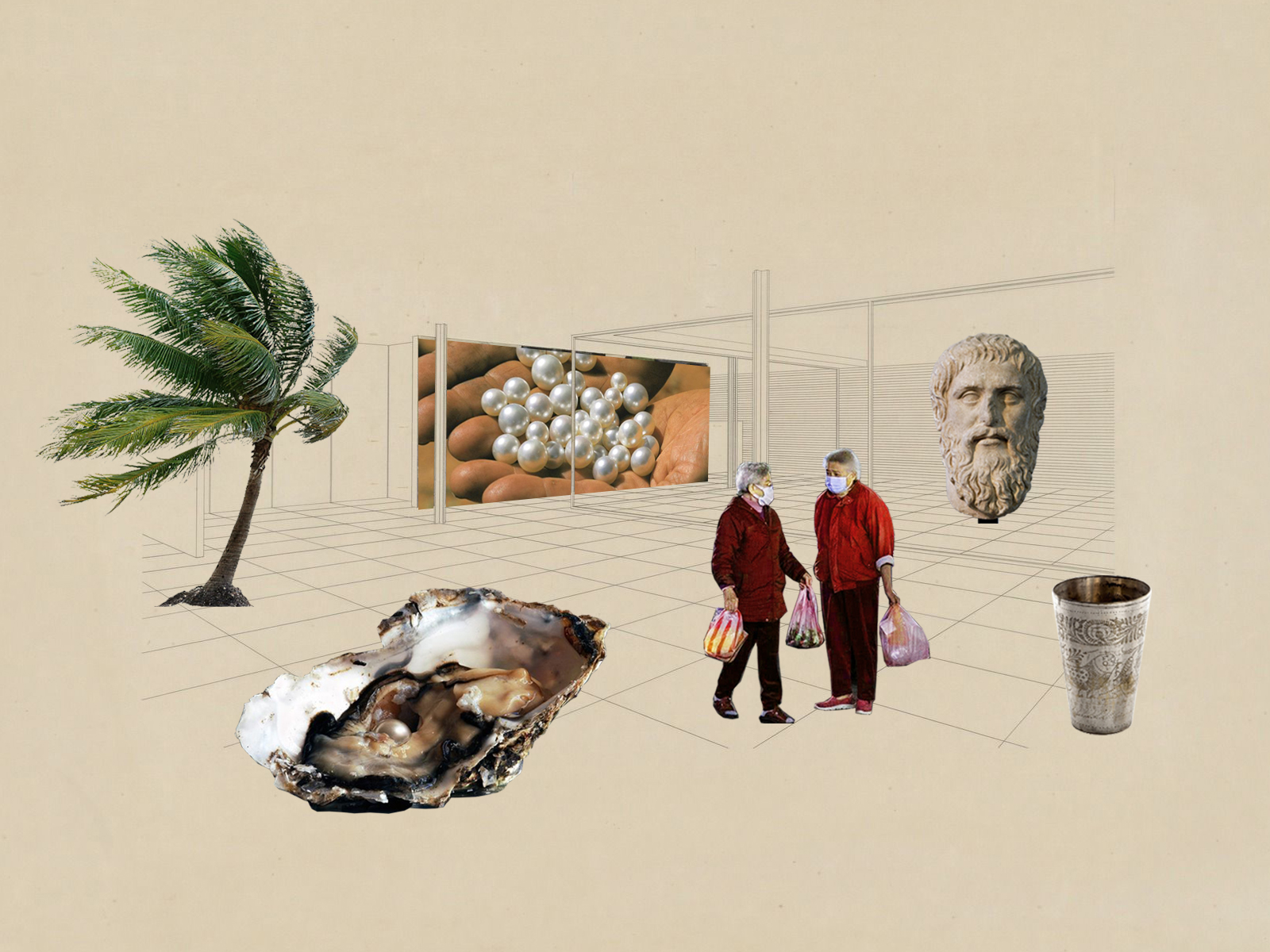

Ann Patchett’s “How to Practice” piece for The New Yorker, describes a desire for living a light life through a personal experience related to death. When Ann had to help her childhood friend Tavia clear out her deceased father Kent’s home, it caused them both to reevaluate the amount they accumulated in their life, and what they really needed:

“I started thinking about getting our house in order when Tavia’s father died…How had one man acquired so many extension cords, so many batteries and rosary beads?

Holding hands in the parking lot, Tavia and I swore a quiet oath: we would not do this to anyone. We would not leave the contents of our lives for someone else to sort through, because who would that mythical sorter be, anyway?”

In terms of making climate-based decisions within our lifespan and for our afterlife, Ann’s experience forces us to consider what we would leave behind and what we truly need to hold on to or let go of in our day to day lives. Of course, to have a choice of what to own, is to have the privilege of options in the first place, let alone the ability to accumulate “too many things.” Questioning what we collect over a period of years, let alone a lifetime, may be hard to grasp given the emotional attachment we have to books, art and other objects that hold dear memories. These are crucial to the human experience. However, could we challenge ourselves to design a better way of living and dying, in the spirit of Ann Patchett’s piece, so we leave only the most beloved items behind? Would creating a culture around periodically reviewing what we own and planning what we need to leave when we die, have a positive effect on the environment?

How can designers demote consumption and promote lightness as a way of life? In Paola Antonelli’s words “leave a legacy that means something.” As curator of the ‘Broken Nature’ exhibition (Mlian, 2019) Antonelli shared her views on how designing an ‘elegant extension’ for humanity, by way of a positive legacy, is grounded in thinking more long term than we have ever before by “taking a very big leap in our perceptive abilities.” Could designers create more methods and tools to track our actions, in ways technology already does in less fundamental online realms, for us to understand the long term impact of our decisions and in turn help us build the legacy we want to leave behind?

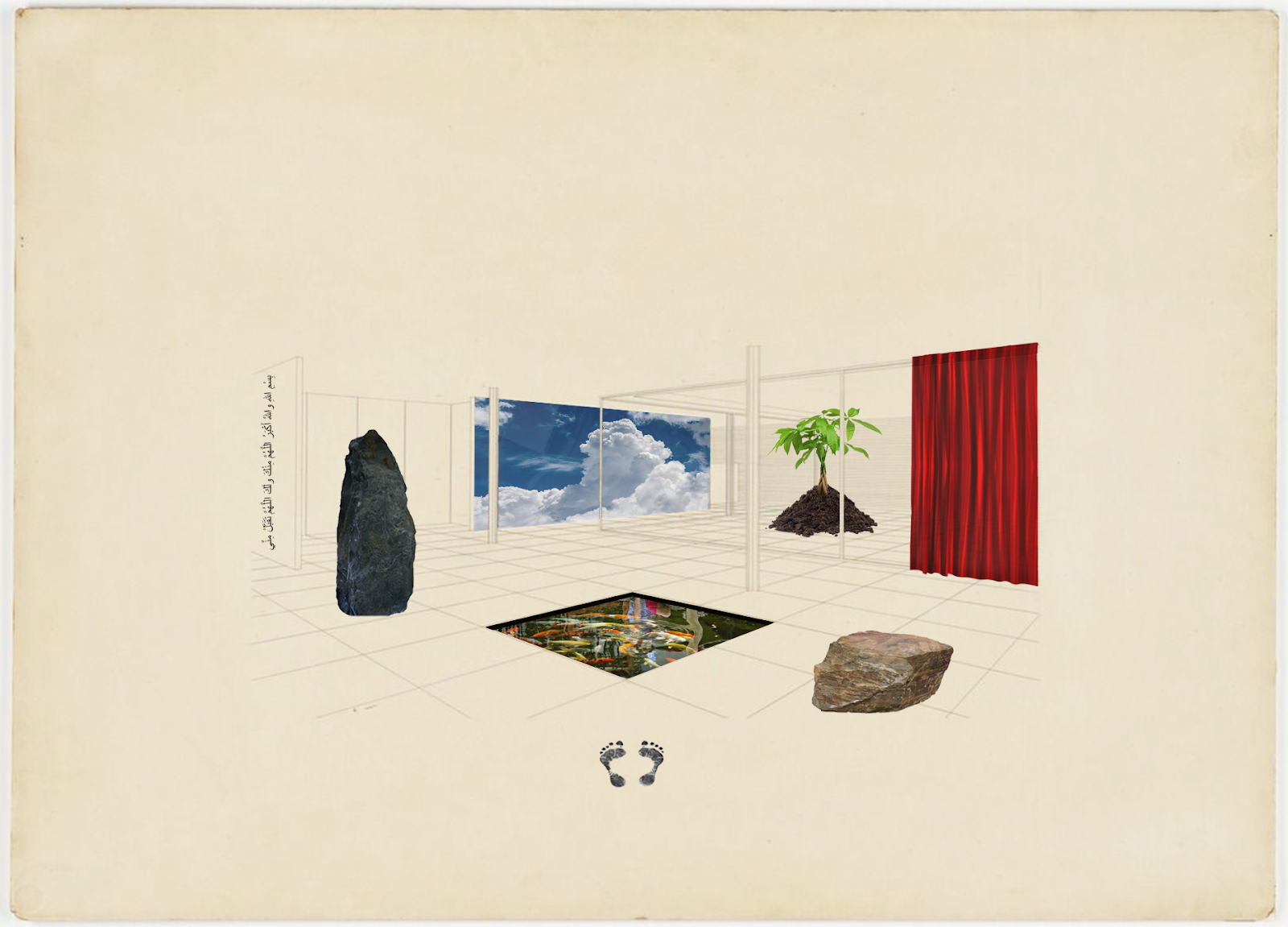

The above Psalm 23 may be familiar to Jewish and Christian communities, as well as Coolio fans. Whatever your spiritual affiliation or lack thereof may be, Psalm 23’s message on guiding light in the depths of despair and proximity to death transcends religion, and its wisdom is available to all of us. “I walk through the valley of the shadow of death” gives us permission to use our awareness of the shadow of death to immerse ourselves in the illuminating light of life. Beyond the “light” mentioned representing good conquering evil and God’s guidance, it’s worth extending this definition to lightness of life, or lightness of being in proximity to death.

Lightness of being in this case refers to moving through the world in the following way:

- with far less attachment to the objects we build up over time

- buying as little as possible

- leaving as little waste as possible

- accumulating and little as possible before we leave this earthly plane

Would designing lighter lives for ourselves, and radically minimizing the evidence of our existence on earth, “our footprint,” be the best thing we can offer Mother Earth in our lifespan and after our death? It seems counterintuitive to the human need and desire to want to leave an impact, or make a difference in our lifetime, however who is to say these have to be linked to materiality and a strain on resources?

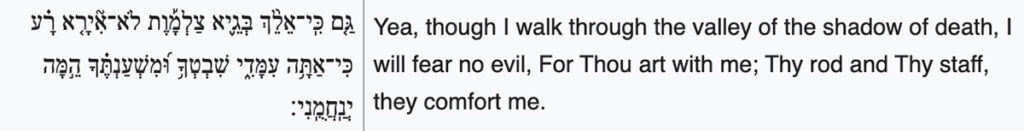

In Milan Kundera’s book The Unbearable Lightness of Being, the story’s thematic meditations open up an alternative to the idea that the universe and its events have already occurred and will recur. Instead the story emphasizes that “lightness” of being is found through surrendering to the freedom of knowing we only have one life to live, and what occurs in our life occurs only once and never again. Annie Smithers’ book Recipe for a Kinder Life, links such lightness of being to living with gentleness and minimal impact on Mother Earth. Annie’s guiding words reveal that the key to living a more environmentally conscious and lighter life is grounded in finding the best way to care for yourself.

One of the purest forms of self care is healthy sustenance. Kitchens are havens for such sustenance, and often teach us about death and the value of life, even if indirectly. One of my abuela Leonor’s cookbooks for a roast chicken recipe stated as the first step “1. Kill the chicken” followed by advice and how to do so. This felt fairly comical to me as a kid, growing up in North West London, far from the experience of Colombian fincas my grandmother grew up on. Whether you are a meat eater, pescatarian or vegetarian—death, albeit to very different degrees—plays a fundamental role in the sustenance of our lives. Halal butchers will say a prayer to Allah before slaughtering animals, or have it written on the walls that witness their taking of life, in acknowledgement of the sustenance they believe to be given by God. From the food we eat to the materials we use, unless we regularly work with land and animals, we’re largely removed from the source of extracting the raw ingredients that nourish us and let us create. We don’t regularly acknowledge that death, in some shape or form, is a necessary truth behind our existence. It’s near impossible for all designers and chefs to be personally responsible for extracting the raw materials we work with. However, making material and ingredient traceability a central part of any design and cooking process has the potential to interweave an appreciation and respect for past life cycles, without which we would not be able to make or eat. Our health and that of our planet would likely benefit as a result.

Composting sheds a distinct light on how the ingredients of death after a meal preparation, in the form of unwanted organic waste, can give new life through its return to the earth and nourishment of soil. Composting presents an opportunity to redefine the lifecycle of objects we use that don’t need to last a lifetime or more, but could purposefully and carefully be broken down after use. By contrast, for those objects we desire to last as long as possible, designers have the capacity to combat the planned obsolescence responsible for so much pollution. Planned obsolescence is a policy of producing consumer goods that rapidly become obsolete and so require replacing, achieved by frequent changes in design, termination of the supply of spare parts, and the use of non-durable materials.

Planned obsolescence is at the core of Apple’s practice. My small form of cost-saving protest to this involved replacing the battery in my iPhone 7 for $50 to make it last as long as possible. It wasn’t until last month that I succumbed to an iPhone 14, and had an honest conversation with a kind Apple employee about the almost comical nature of new phone releases and their minimal differences regarding what we really need and the psychological impact of “superiority” by having the most up to date technology. This is by no means a form of self praise (as I type this on my MacBook Pro) but an example that aims to demonstrate how we can challenge ourselves and the consumer decisions we make. In an attempt to combat planned obsolescence, the Right to Repair Law was passed in Europe last Spring. It requires electronics such as washing machines, televisions, and hair dryers sold in the E.U. to be designed to allow for easy repair for at least 10 years after the product comes to market. This legislation purposefully prolongs a product’s durability and repairability while minimizing e-waste, (additional upcoming legislation in the E.U. focuses on smartphones and laptops, which account for a large portion of global e-waste.) However, could access to easy repair be even longer than a 10 year period? Probably. One of the most straightforward ways to fulfill these new requirements (and take them further), is to make sure that design for disassembly is an integral part of the universal design process and design education.

Composting and combating planned obsolescence have an important principle in common. Whilst the former naturally decomposes to give new life, and the latter is about extending the lifespan of an object, both practice care for future generations and the future state of the planet beyond our time on earth. Whilst manufacturing related legislation is a fundamental starting point, we can also take inspiration on how to care for future generations through other forms of local government initiatives and legal action. Take the Welsh Government’s Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act founded in 2015 or the 16 young people in Montana, USA ranging in age from 5 to 22 who are suing the state in a climate change trial this month, arguing that Montana’s use of fossil fuels is “destroying pristine environments, upending cultural traditions and robbing young residents of a healthy future.” Beyond the crucial protection of our ecosystems for a healthy future, the Montana youth also present a robust link between environmental preservation and protection of cultural traditions. What role can design historians play in linking cultural traditions to environmental health in order to secure their longevity and legal safeguarding for future generations, similar to UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage protection?

Designers are agents of change, trained to reimagine the future and decipher between what can be done differently and what should remain protected and consistent. In parallel, designers are also at the epicenter of shaping desirability and purchasing decisions. Whilst designed objects and food consumption are each deeply intertwined with excessive consumerism, they each also have immense potential to make living lightly in respect to death, a desirable and luxurious form of existence. In curator Kyong Park’s words, from his The World Around Summit 2023 talk, we need to question our freedom within the realms of a capitalist structure to demand a culture of conscientious living over excessive consumption. “We are told to recycle and reduce pollution and so on, but few are brave enough to stand up against the ‘freedom’ of consumer choices – our most popular form of democracy…It’s patriotic to buy and buy, and waste and waste. After all, we’re not citizens anymore, just tracked consumers to further income inequality…”

Below you can find a list of articles, papers, experiments and “what if” prompts under a collection titled The Death and Lightness of Being “library” for designers and makers. This list is there to digest, dissect, add to, edit, share and revisit for your own practice—may it take on a life of its own beyond this piece. As a final reflection and call to action, in the words of Maya Angelou, may we recognise and take radical responsibility for the space we occupy, what we create, and what we leave behind.

It’s serious business that’s costing the earth.

Maya Angelou“Every human being has paid the earth to grow up. Most people don’t grow up. It’s too damn difficult. What happens is most people get older. That’s the truth of it. They honor their credit cards, they find parking spaces, they marry, they have the nerve to have children, but they don’t grow up. Not really. They grow older. But to grow up costs the earth, the earth. It means you take responsibility for the time you take up, for the space you occupy. It’s serious business. And you find out what it costs us to love and to lose, to dare and to fail. And maybe even more, to succeed. What it costs, in truth.”

The Death and Lightness of Being “library” for designers and makers

Sources

- How to Make the World a Better Place, Nicholas Kristoff, The New York Times

- JB MacKinnon on ending overconsumption, Jamie Waters, The Guardian

- Community Fridges, reducing food waste and empowering communities

- Buy Nothing Groups, their appeal goes beyond the chance to swap everything

- 9 things you can do about climate change, Imperial College & The Grantham Institute

- When less is more: minimalism and the environment, Crisol Lopez Palafox

- Falling in and out of love with stuff…decluttering in Japan study, Fabio Gygi, SOAS

- The Circular Economy: design for disassembly, Courier issue 44

- Designing to live with waste, artist Andrea Ling

- Sustainable homes are here, but at a premium cost, The Financial Times

- Redesigning Death case study, IDEO

- Mushroom burial suit, artist Jae Rhim Lee

- Loop’s mycelium coffins, Wired

- Start-ups wanting to make death greener through human composting, The Guardian

- Death by Design, a documentary on devices designed to die

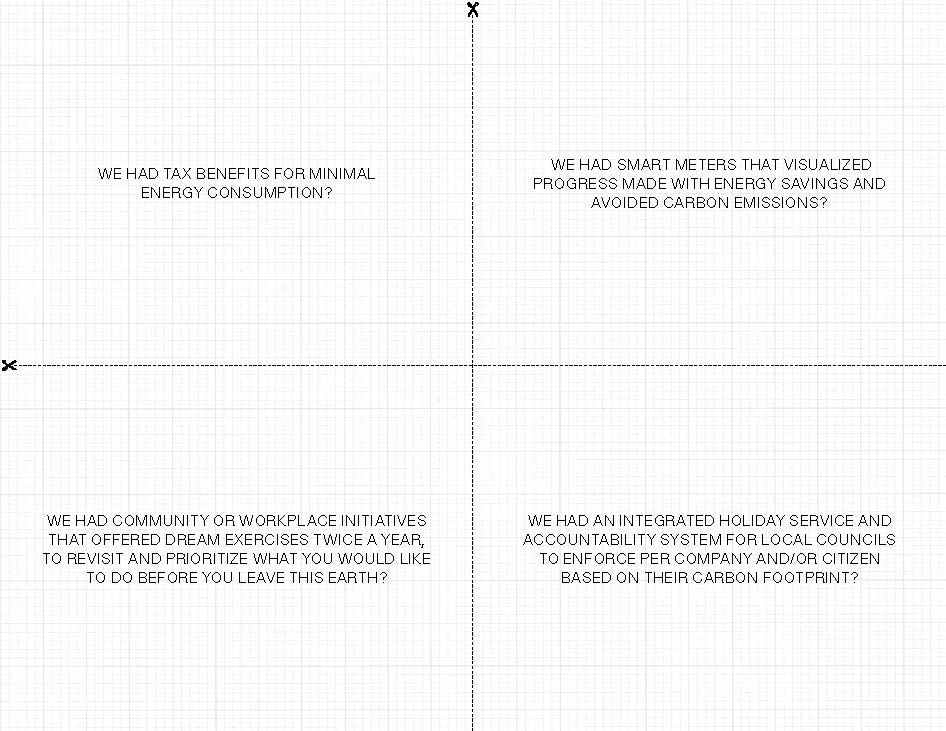

- We had government funded personalized eco-consultation services to provide step by step actions on how to minimize our carbon footprint? E.g. bi-monthly visits from an environmental energy expert, according to your household income, size, house type etc.

- We had funding pools for retrofitting homes with energy saving appliances?

- We had carbon reduction competitions by borough, gamifying the carbon reduction process?

- We had tax benefits for minimal energy consumption?

- We had smart meters that visualized progress made with energy savings and avoided carbon emissions?

- We had community or workplace initiatives that offered dream exercises twice a year, to revisit and prioritize what you would like to do before you leave this earth?

- We had an integrated holiday service and accountability system for local councils to enforce per company and/or citizen based on their carbon footprint? E.g. You’ve used X amount of energy over the last 6 months, well above your recommended amount, consequently you’re only allowed to take one return flight in the year 2024. We recommend these holiday destinations all accessible via train.