When artist Mary Mattingly’s last apartment kept flooding, she was struck by how porous the building suddenly seemed—“There was water pouring in from everywhere; the ceiling, the roof, through the walls.” An ensuing stress dream featured an Escher-like building in an endless cycle of repair and decay, with water collecting in all its crevices. It was this image that became the basis for Mattingly’s newest exhibition, Ebb of a Spring Tide, at Socrates Sculpture Park. Through a series of site-specific works, this vision of apocalyptic limbo is transformed into fertile ground for a new future.

At the center of the installation is Water Clock, a 65-foot tall sculpture that traces the squared contours of the Manhattan skyline. A direct translation of Mattingly’s dream, water from the nearby East River, stored in 55-gallon drums atop the structure, drips through a scaffold of steel beams and wooden planks. The amount of water that seeps through Water Clock waxes and wanes, ebbing in time with the tide thanks to a computerized motor. Flowing through an eclectic series of tubes and funnels, it trickles between the scaffolding onto an array of salt-tolerant, edible plants. The wild bergamot, verbenas, and indigo are the new tenants of this apartment.

Faced with the increasingly volatile forces of nature brought on by anthropogenic climate change, our seemingly solid structures often reveal themselves to be all the more transparently hollow. Like much of Mattingly’s practice, this exhibition works overtime, both identifying problems of ecology and the environment while offering potential curative alternatives—all with her characteristic sense of joy, community, and most urgently, hope. In doing so, she follows in the footsteps of artists like Agnes Denes, Mel Chin, and Maria Thereza Alves who have long recognized that it is not enough for artists to simply point to an ill; it is the artist’s distinct power to imagine something beyond it.

For example, one of Mattingly’s best known works, Swale (2016-ongoing), both underscores and responds to an inane, century-old New York State law that makes it illegal to grow or pick food on public land. Racist and classist in its undertones, the law was ostensibly passed in order to protect ecosystems from foragers.

These foragers would have been mostly low income and people of color; particularly Black and Indigenous populations. Anti-foraging laws like the ones upheld in New York go hand-in-hand with historic redlining which has resulted in the current dearth of grocery stores and fresh food access points (aka: food deserts) in these very same communities.

By situating an edible and medicinal foragable garden on a floating barge as a commons in the East River, Mattingly was able to subvert the law of the land by turning to the law of the sea; there is no mention of foraging in maritime law. Swale has since inspired the creation of NYC’s first public foodway, the Bronx River Foodway, which opened in 2017.

Tracing a circular path in the center of Socrates Sculpture Park, Ebb of a Spring Tide’s plantings are in many ways an extension of Swale, inviting visitors to learn and forage from the brackish flora. In fact, when the exhibition is deinstalled this fall, these plants will be transplanted and live on the barge; Swale closed during the pandemic and is currently being redesigned into a more permanent structure called Lotic Shoal, set to launch next summer.

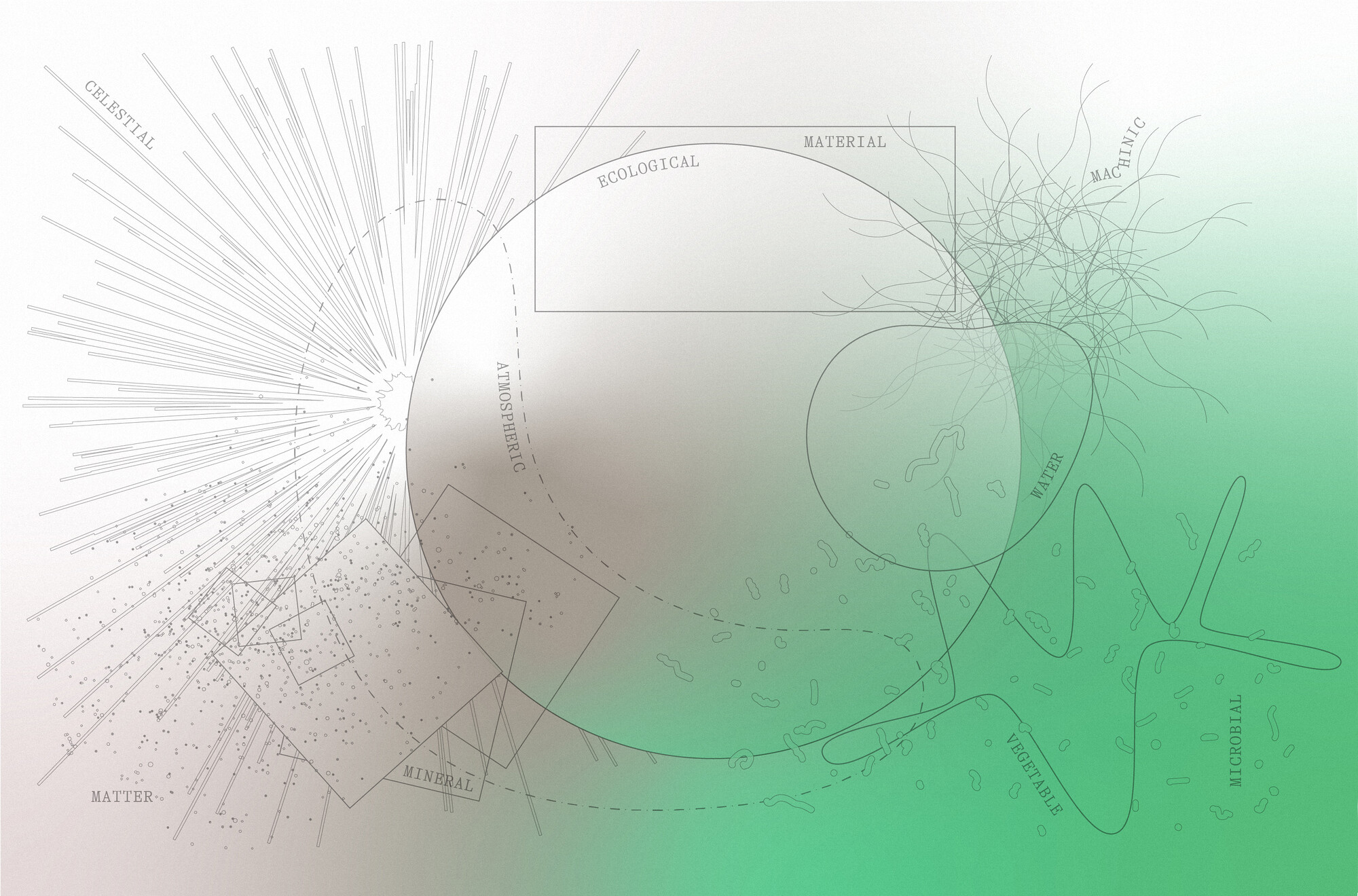

Continuing along the circular path of these plantings extending from Water Clock is a half-buried canoe and a geodesic, space-station-like dwelling titled Flock House. When seen from above, the arrangement begins to echo a kind of planetary system. The overhead view of Water Clock is based on the East River’s tide map while Flock House appears like a moon and the canoe a satellite stuck in orbit.

Part of Mattingly’s ongoing practice constructing self-sufficient dwellings, Flock House serves as an adaptive habitat, housing workshops on natural dyes and anthotypes (using plants to develop photographic prints). The space will also be Mattingly’s home and studio through the month of August.

In another act of subtle subversion, by living in this makeshift moon, Mattingly asks us, a predominantly solar-oriented society, to consider the power of this smaller, more intimate celestial body. As such, Water Clock also acts as a lunar clock, tracking time in accordance with our planet’s relationship to the moon.

Ebb of a Spring Tide beckons us to consider alternative realities that focus on, steward, and cherish all that is already near. “I believe when a human-made ecosystem is small enough to comprehend, it opens up more opportunities for care,” said Mattingly in a statement about the exhibition. “I believe when a human-made ecosystem is small enough to comprehend, it opens up more opportunities for care.”

In 2015, Mattingly penned a manifesto of six tenets that outline her vision for art as a mode of utopian thought. The fifth point in the manifesto identifies the problem of our violent social order. Mattingly, however, takes care to articulate this not as a source of despair but of insight: “Collective traumas are known to change our collective sense of what’s possible,” she writes.

In Ebb of a Spring Tide, Mattingly excavates her own personal trauma of climate change-instigated housing insecurity in order to imagine collective possibilities for how to navigate the future and the present.