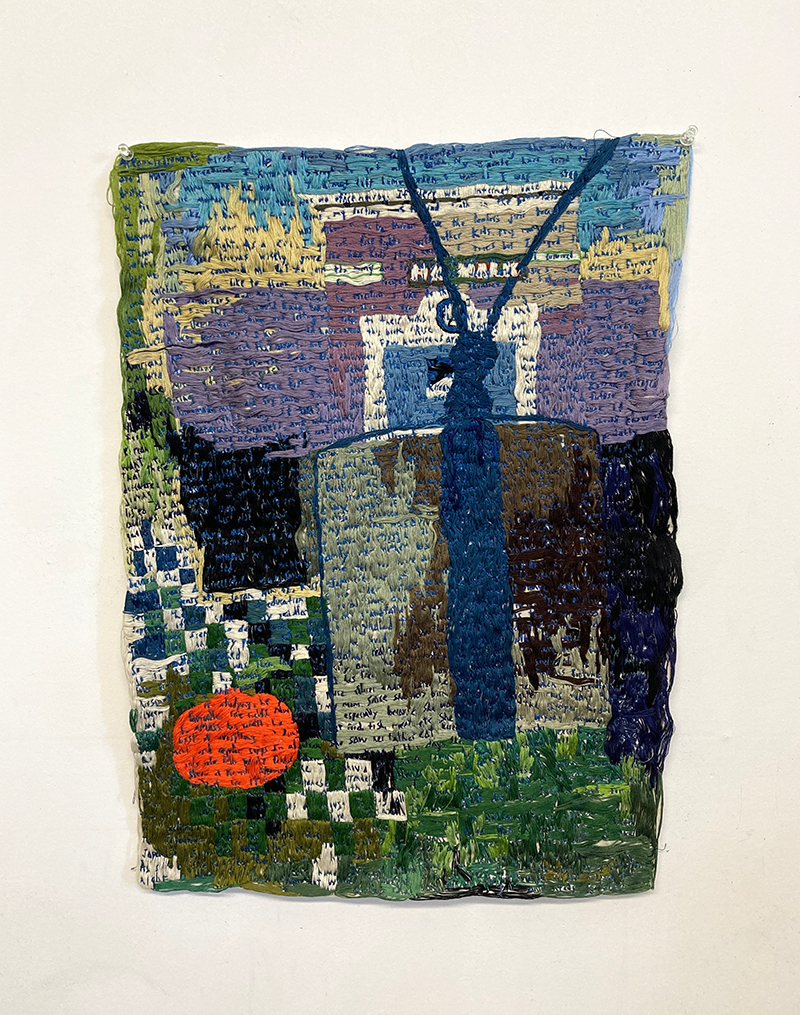

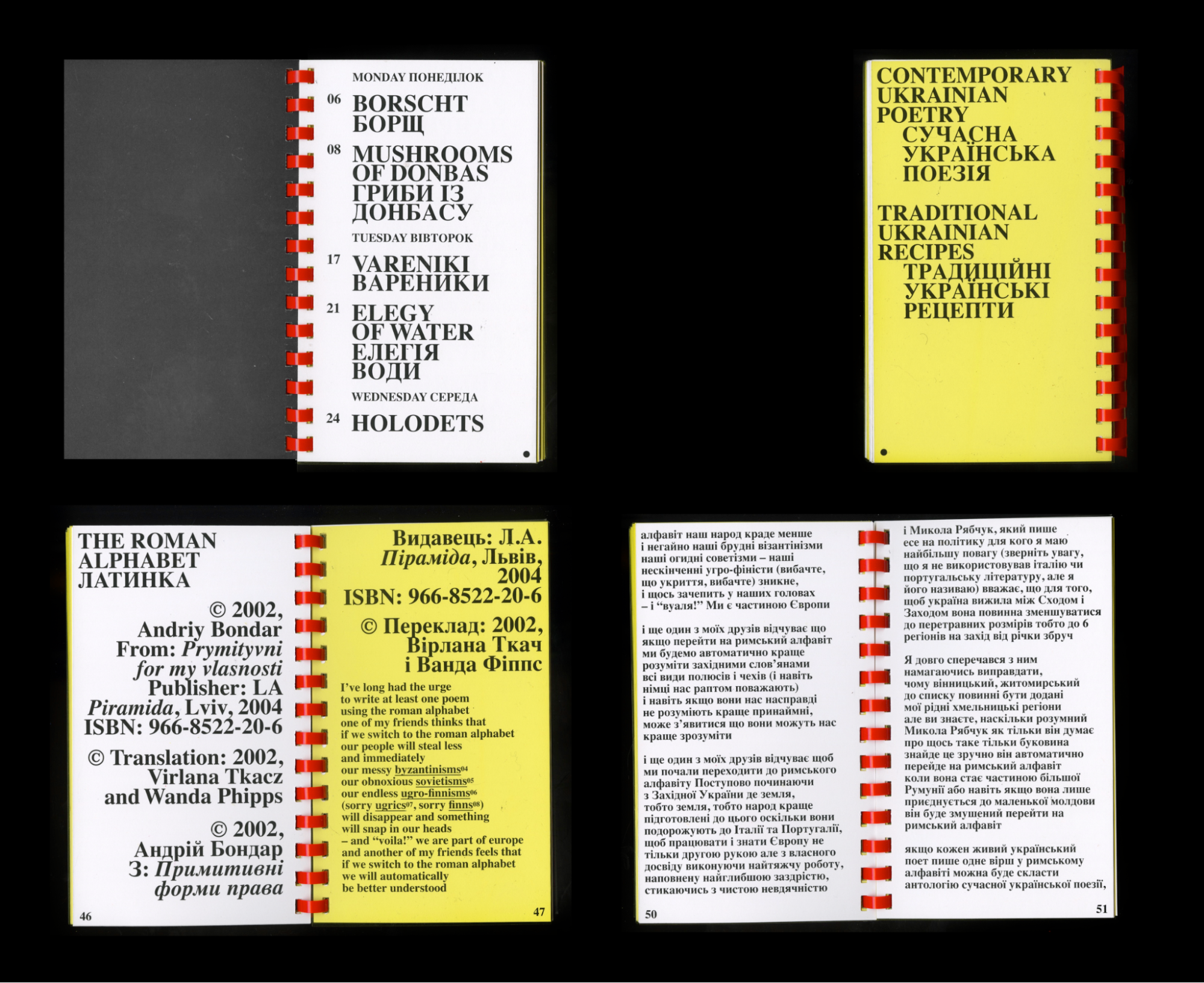

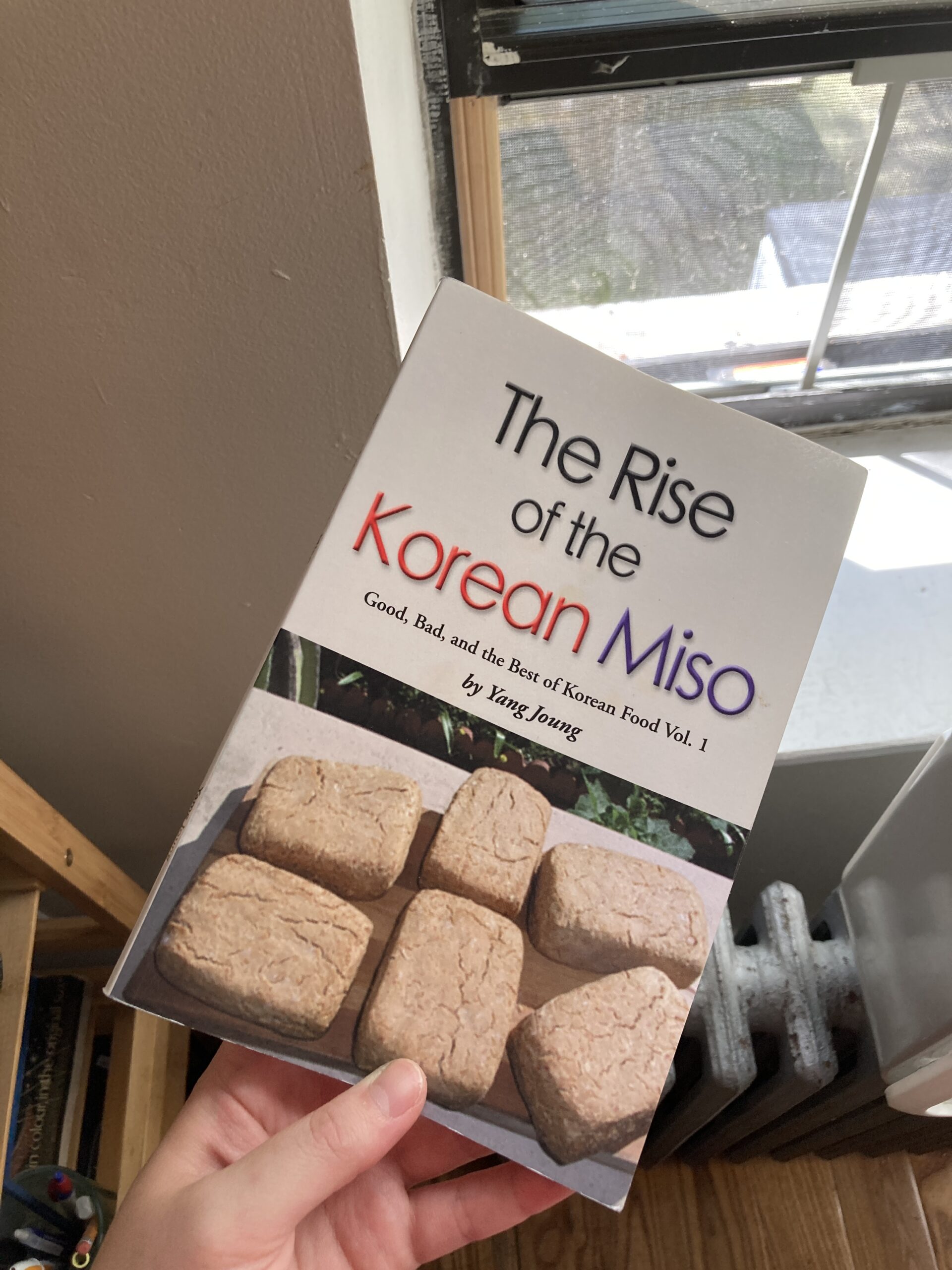

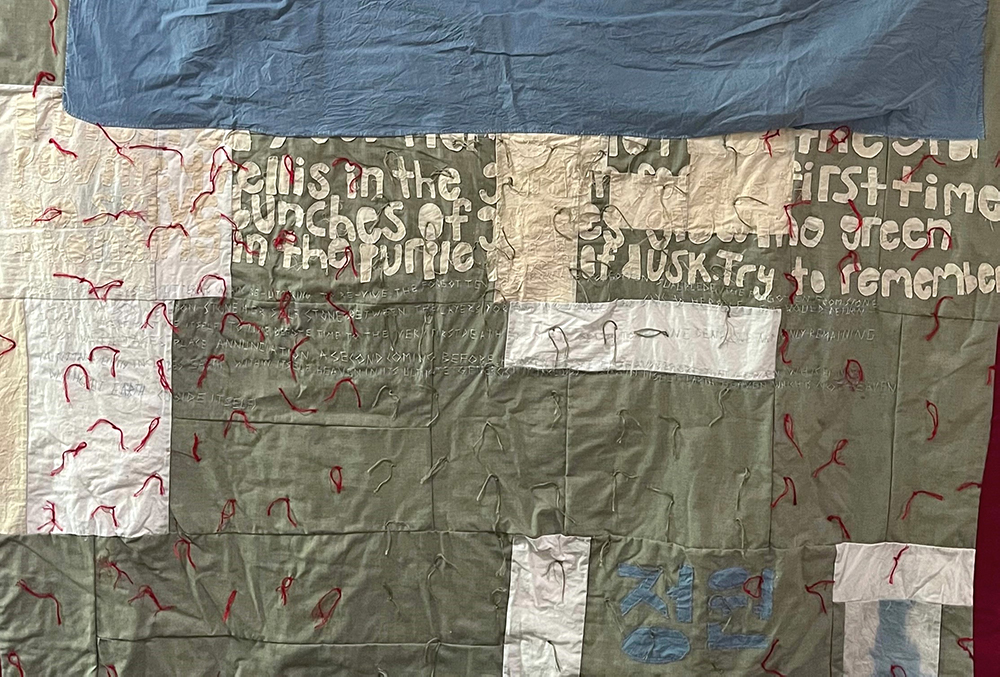

In a recent textile work by artist Young Grace Cho, a meju block — the starting point for making doenjang, a fermented soybean paste — is shown suspended in the foreground, embroidered and embedded in a sinuous collage that includes stitched text from Yang Joung’s The Rise of Korean Miso and a depiction of Glendale, California landmark HK Market. For Young, who is also the current Head of Pastry at Yellow Rose, food has always served as a handy vessel for storytelling. Earlier this summer, Young and I sat down to talk about their practice. In this conversation, I speak with them about the role of maintenance and memory across their myriad practices, collecting community cookbooks, and excavating the internet as an archive.

Isabel Ling:

Tell me a little bit about this textile work you’ve created.

Young Grace Cho:

It’s a hand-embroidered piece, with the introduction of this sort of cookbook memoir that I found called The Rise of the Korean Miso transcribed and layered across an embroidered image of HK Market, this grocery chain from the West Coast. And this is a meju block, it’s part of the initial process of making doenjang, a fermented bean paste which is what “Korean miso” is. To make it, you grind up the soybeans into a paste and form it into blocks before hanging it to dry for several weeks. You hang it up with a handmade rope of rice straw, and that’s how the block is basically inoculated with bacteria for fermentation.

IL:

How did you find out about this book?

YGC:

I actually found this book in Archestratus. This was just in their general Asian section, which had like six books. This one stuck out to me because I’ve wanted to make doenjang for a long time and there were great photos. The phrase “Korean Miso” also stood out as an interesting choice and I was curious who the author was writing this book for.

And also I felt like a little bit of a connection with the author, too. My family moved to Glendale, California in 2008. The book came out in 2009 and around the same time, Yang was writing about making doenjang and cataloging his favorite grocery stores and Korean barbecue restaurants in Los Angeles. And of course, he mentions HK Market, which was in part, a big reason why my family moved to Glendale. He lists it as one of the better LA-area places to buy Korean products when he does a full review of all the grocery stores in LA. He also mentions keeping a food diary on a blog, which I found using the Wayback Machine, and it describes what I think of as the diet of every 2000s LA Korean: doenjang jjigae, Costco pizza, Hot Dog on a Stick, several kinds of Korean cold and hot noodle soups, and King Taco.

For him, making doenjang has been a practice he’s participated in for over 20 years. I think it’s admirable because it’s important for cultural memory and preservation of craft. But also, I think it’s important to eat certain foods that your family and your ancestors have eaten, something that he echoes in the book as well.

IL:

Is this self-published?

YGC:

Yeah, he published it himself.

IL:

Have you thought of reaching out to him at all?

I did! He’s actually pretty online, he’s worked in online food distribution for awhile and also ran this website called ramencity.com. I emailed him and he responded almost immediately. If you read the book, you’ll see that he has his website and email address throughout almost every chapter of the book, and he’s like, ‘If you want input on this recipe email me, please let’s be friends.’ And he still has the same email address.

This is his response:

Young, thank you for writing me. Ever since I went through financial hardship, I do not make doenjang. But I do make Korean recipes. You can check it out on Tik Tok at Bloodofkhan. Anyway if somehow I’m able to make doenjang again I will let you know, send pictures also, if you decide to proceed to make it; smiley face. Hope you the best, Yang. Sent from my iPhone.

IL:

Have you made doenjang?

YGC:

Not yet, it takes almost a year to make and I haven’t really been in an apartment where it makes sense to make it. It also requires outdoor space, you’re supposed to hang it from the rafters of your home. And it’s somewhat expensive to make, and also smelly. It does make two products, doenjang, or the soy bean paste and then it also makes this soy sauce that is really rich and can be used for soup bases.

IL:

So tell me a little bit about what inspired you to bring Yang’s writing to life through your art-making practice?

YGC:

I’ve done work with transcriptions, embroidery and text in the past. For this piece, I really wanted to do a larger work where I was transcribing a bigger piece of writing. I was really drawn to this book because I collect community cookbooks. My favorite part about them is the little blurbs from the contributors about their lives and the context of their recipes, where they got the recipes from, and the anecdotes that give you a broad picture of who this person is and why this recipe is important. It’s a way for people to describe their lives and how they encounter recipes. When asked to provide one recipe, what is the recipe that they choose? Basically, what foods are important to people, and also how people situate themselves within a community and what they think about their identities.

Across the recipes he also talks a lot about his family’s experience with immigration, colonial collaboration, with the Korean War and his own interests in joining the American military. In the introduction he talks for quite some time about his mother’s role in convincing him not to join the military. This book is an important example of personal memory in the larger context of Korean-American history, and a lot of my interest in this book is in how he combined a historical war narrative with his descriptions of who he is and why he makes food. I think that remembering is especially important for Korean Americans, because the Korean War is not a part of the American public memory. We live in a nation that is trying to forget its active involvement in the conditions that led many Koreans to immigrate here, and which would like us to forget, also.

In all my embroidered transcriptions, I am not directly transcribing the text, I am editing and reorganizing the text. I originally started with poetry, mostly a book called The Hundreds by Kathleen Stewart and Lauren Berlant, as well as the book Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. At the time I was thinking about their legacies, Berlant died in 2021 and 2022 was Cha’s 40th death anniversary, and about how they organize text in each book. And I think besides what the words say, my favorite thing about writing is the way the words look, the choices people make about how to structure their sentences and paragraphs. So I like writing in embroidery for aesthetic reasons. But also I kind of think of it as something similar to engraving or carving in stone, of making something more permanent, or cemented, like a marker or memorial. Like engraving, with embroidery you are permanently altering the material, in this case by poking holes in the fabric.

IL:

How long did it take to make the piece?

YGC:

About 4 months.

IL:

Wow, that’s a long time.

YGC:

Yeah, I’m interested in practices that you have to do every single day. Things like, tending and checking, feeding and cleaning. When I was reading people’s blog posts about their experiences with making doenjang, they talk about having to dust the blocks off every day or having to rotate them. Taking care of a living thing is something that is important in itself. But thinking explicitly about care and maintenance is also an acknowledgement of labor and the fact that these practices can’t be sped up no matter what you do. It’s sort of a way of contending with this immutable force of nature.

I think both in cooking and textile work you are working with repetition and iteration constantly, also farming and gardening, seed saving, things like that. This idea of building off of something you have made to build something new is something I find to be a very impactful way of making.

IL:

Are there any rituals you apply to either your food or art practices? Do you see any overlap between them?

YGC:

Before starting new textile work, I like to spend a lot of time on various archives on the internet. For example, with this work, the grocery store that is depicted in is closed, but all of their business pages are still active. Most businesses have an online presence so you can go on their Yelp pages and all those comments and photos are still there. For research, I love going through YouTube comments and reviews of restaurants, or even the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.

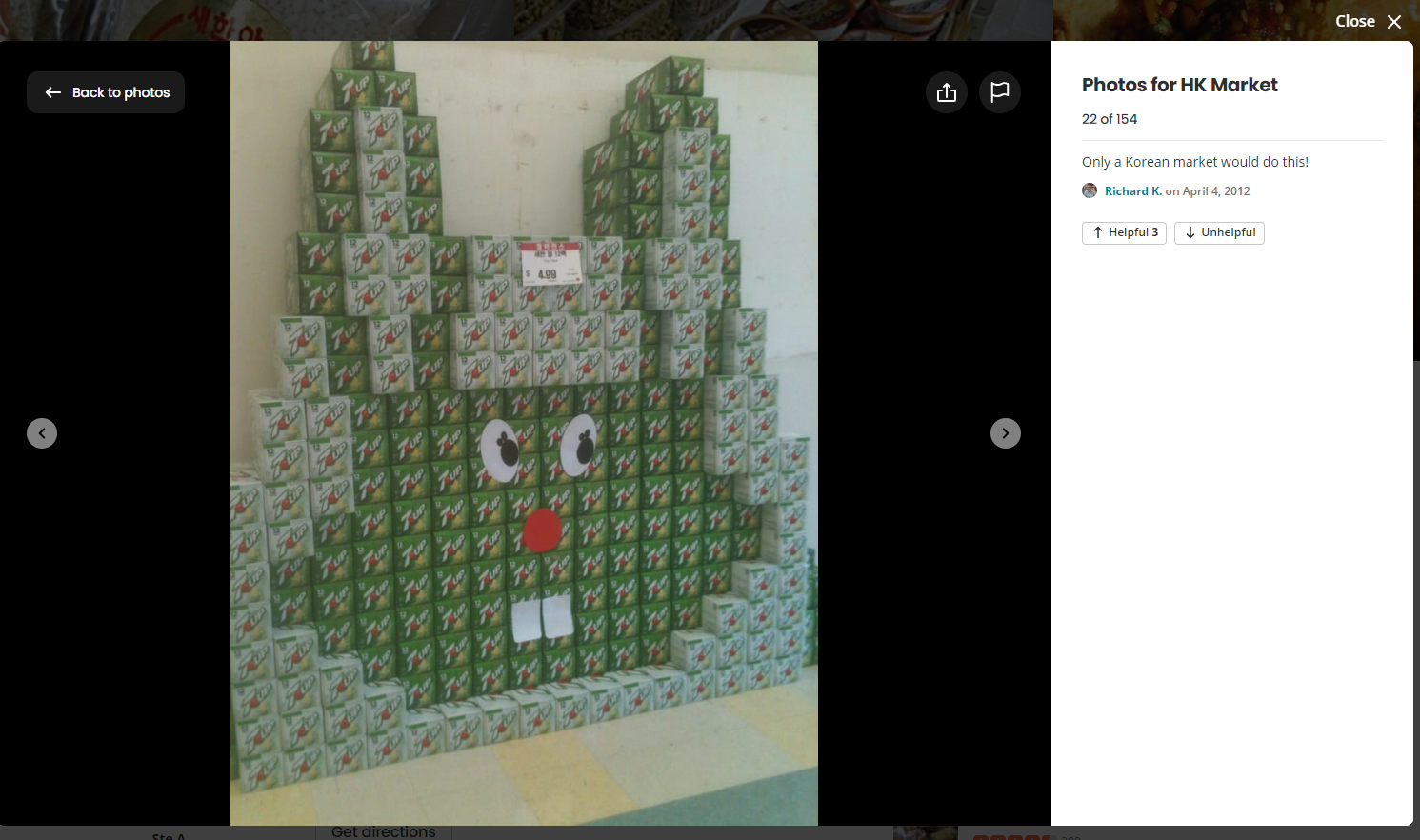

For example, HK market is now an Armenian grocery store called BIG SQUARE. And there’s a clock on the facade of the grocery store, that when I was growing up used to be broken so that it was always 7 o’clock. Part of making this piece, I was really curious to see if they had fixed the clock, changed something that, even though it was broken, gave the grocery store a sense of place. And looking on Google Maps you can see the time has changed and they likely have fixed the clock. There are other things these online archives preserve, like the painted cityscape on the walls or the tiles of the floor, even the displays.

These are the sorts of things that help ground my work and help me think of my work as situated in an archival and historical practice. I think of my work as informed by an unstructured archive, a collection of points that are spontaneously created by individual people whether or not they are intending to or probably don’t think of it as archival work. Importantly, most of these online archives that I’m referring to are not permanent in any sense, are managed by private companies, and can be deleted at any time.

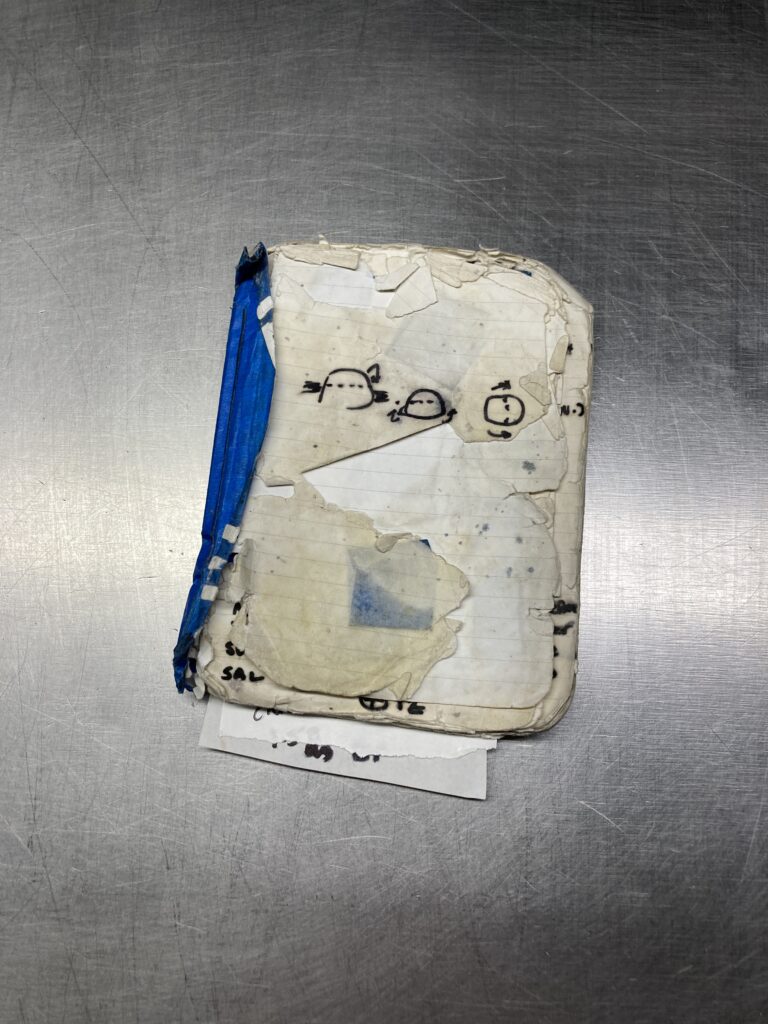

In terms of food, I have a really disgusting little recipe book that I carry around work. This is maybe the third iteration of this book. And it’s fallen apart so many times, it’s held together by blue painters tape. I use this for everything at work. Even when I have recipes memorized, I still refer to this book. It’s like this pastry neuroticism, making sure that your mind is focused and having that ritual of referring to a physical object every time before you make something new. With pastry, it’s very easy to lose focus and get confused. Going back to this concept of time, with pastry a lot of these things take time and when you mess up in the beginning, it’s almost impossible to recover, depending on what you make. So having that care when you start something is an important ritual in pastry work.

IL:

What is this pastry neuroticism, exactly?

YC:

I like to claim that I know that the timer is going to go off before it does. No one at work believes me [laughs], but at this point, I like to think I have an internal timer. And that neuroticism comes with the craft, almost, I think, it’s a way of always knowing where you are. Pastry requires so much precision, it’s what drew me to it.

Before I worked in food, I worked in science, I worked in suicide research and in public health implementation research. Science research requires precision and planning, and a pretty rigid way of thinking, and so I think the transition was easy for me.

IL:

What made you make that transition from science to food?

YC:

I was working in mental health research. I went to school for psychology and neuroscience, and right out of college I was working in the field. But during COVID, I started to feel very alienated from my work and was having a hard time connecting to what I was doing on a daily basis. I think it was not so much. because I was working in mental health, but because I was working in research in an academic facility. And so it forced me to think about what I wanted to do on a daily, hourly basis. And I realized I wanted to be making things. I’m interested in making a lot of different things. But the reason I went to food, is in part because I love food, I’m very interested in it, but also partly because on a practical basis, it’s one of the easiest fields to get jobs in. Getting a job in art is a little more difficult.